Sindre Hovdenakk (f. 1964) er sakprosaforfatter og kritiker. Han var Prosa redaktør i perioden 2014–2019.

Teksten er publisert på norsk i papirutgaven, men ble oversatt til engelsk for digital publisering i forbindelse med Norges status som gjesteland ved bokmessen i Frankfurt i oktober 2019.

A raven, a road trip in Poland, Norwegian-Americans and strong wills. The history of Norwegian non-fiction’s breakthrough on international markets is as complex as the literature itself.

This month, Norway’s publishing people will flock in their hundreds to Frankfurt to take part in the big literary event of the autumn: Norway is guest of honour at the world’s most important book fair. This marks the culmination, for now, of years-long efforts to promote, disseminate and raise the profile of Norwegian literature abroad. The Frankfurt project, which Jan Kjærstad has sarcastically dubbed F 2019, will display both the breadth and the heights of Norwegian literature. And non-fiction has an indisputable and uncontroversial place in this picture. But if we look back, it was far from a foregone conclusion that non-fiction authors would now be standing shoulder to shoulder with their fiction-writing peers at the book fair’s cocktail parties and on the shelves of the publishers’ stands.

100,000 kroner

“The interest among Norwegian publishers was extremely modest, to put it mildly.”

These are the words of Trond Andreassen, who was secretary general of the Norwegian Non-Fiction Writers and Translators Association (NFFO) for many years. He is speaking about the situation in the mid-1980s, when the NFF, as it was then called, was keen for Norwegian publishers to use compensation funds to finance a project to “disseminate information about Norwegian non-fiction abroad”. It was unsuccessful. Instead, it received 100,000 kroner in 1984 for what was termed concrete marketing efforts. This initial investment would lead to more systematic work, driven by the NFF, on how such marketing would be organised in the future. But there was still little sign of enthusiasm, either from publishers or the board of NORLA (Norwegian Literature Abroad). The organisation had existed since 1978, but clearly failed to see non-fiction – or specialist literature as it was then called – as a natural area of focus. A plan by the NFF to co-fund a position devoted to pursuing this work with publishers ran aground because it was impossible to obtain state guarantees for the business. A further ten years would pass before a dedicated non-fiction organisation was in place.

The Norseman

With Trond Andreassen at its head, the NFF nonetheless continued its strategic efforts to promote Norwegian non-fiction abroad. In 1989, the organisation contributed to a special edition of NORLA’s magazine, News from the Top of the World, but this was never repeated. Again, the problem was funding, but the following year, an interim solution was found. The Norse Federation, an organisation for Norwegians and their descendants overseas – especially in the US – came on the scene. Over the next five years, the federation published special editions of its magazine, The Norseman, devoted to Norwegian literature. Including non-fiction. It almost goes without saying that secretary general Trond Andreassen sat on the editorial board.

But when the last of these issues, called Norwegian Literature, appeared in 1994, Andreassen was on his way out of the NFF. He spent the next couple of years, before returning to the association, as the head of the university and university college department of Universitetsforlaget, the university press. And during this time, he had some interesting experiences with editors at the Norwegian publishing houses.

“They weren’t very good at considering whether their books might have an international appeal. I tried to make them aware of it, but it was tough work. It wasn’t just that we lacked awareness of this issue. We lacked an institution.”

The Raven Has Landed

A new joint funding team was needed: with contributions from the NFF, Arts Council Norway and Andreassen’s employer, Universitetsforlaget, MUNIN was set up in December 1995. For an initial trial period of three years. The acronym stood for Marketing Unit for Norwegian International Non-fiction and it shares its name with one of Odin’s ravens. The other one is called Hugin. According to Norse mythology, these two ravens fly out into the world every day to find out what’s happening, and at night they land on Odin’s shoulders and tell him about everything they’ve heard. That is what makes Odin the most knowledgeable of all the Norse gods.

In other words, there were grounds to hope that MUNIN would fly high from day one. But the interest from Norwegian publishers was more vague than committed, according to Elisabet W. Middelthon. She was MUNIN’s first – and for many years only – employee.

“Positive but not especially enthusiastic, without any particular expectations.”

This is how Middelthon sums up the attitudes she encountered to her work in Norway. Few people in those days had much faith in the idea that there was a market for Norwegian non-fiction overseas.

So what did they do next, now that the institution was set up in Norway? They built networks out in the wider world.

To Poland

“At one point, I packed my little car full of publishers’ catalogues and other material and set off on a tour of Polish universities. The 1990s were a time of openness and there was a great deal of interest in cultural exchange between east and west. At many of the old universities there were groups with an interest in Norwegian and Nordic studies. So it was a matter of building contacts. I gave lectures about Norwegian non-fiction, got tips about publishers that might be interested in Norwegian titles and – not least – I recruited translators. I was also able to invite many of them to visit Norway. And in this way a non-fiction translator community gradually grew.

Not just Poland but the Czech Republic and several of the other Eastern European countries have a long tradition of teaching Norwegian. But Germany is and remains the most important market of all,” Middelthon emphasises.

Soon she was able to present figures that showed a significant increase in foreign sales of Norwegian non-fiction outside the Nordic region. After the first five years, the number had risen from an average of 16 books per year before MUNIN’s launch to an average of 25 books with translation support from MUNIN. The number of applications for translation support was even higher, though: an average of 42 books per year.

Even so, it would be six years before MUNIN was finally incorporated into the state budget.

Masses of men

So what kinds of non-fiction books were being sold to the big wide world towards the end of the last century? For many decades, they were mostly books about the great, male adventurers and polar explorers. With Fridtjof Nansen and Thor Heyerdahl as the obvious leaders of the pack. But in the 1990s, an interesting shift occurred.

“There were two main fields that proved to be in demand out there: one was humanities, especially philosophy and social sciences. The other was medicine, especially nursing,” Middelthon says.

One quite exceptional success was Gunnar Skirbekk’s Filosfihistorie (A History of Western Thought), which was sold to Suhrkamp, the prestigious German publisher. It was also translated into ten other languages, including Russian, Chinese, Uzbek, Tajik and Turkish. A book that has travelled the whole of the Silk Road, as the author himself put it.

Criminologist Nils Christie is another Norwegian scientist who enjoyed international demand in the 1990s. Indeed there was also interest in new biographies of Norwegian scientists in those days. For example Arild Stubhaug’s books about Nils Henrik Abel and Sophus Lie.

And we haven’t even mentioned Jostein Gaarder’s Sofies verden (Sofie’s World) yet. Of course, it ended up being classified as a novel, but it was used by many universities as part of the curriculum for the obligatory elementary philosophy course. According to its publisher, Sofie’s World has been translated to 64 languages and has sold more than 50 million copies. Here, too, the German edition opened the door to the rest of the world.

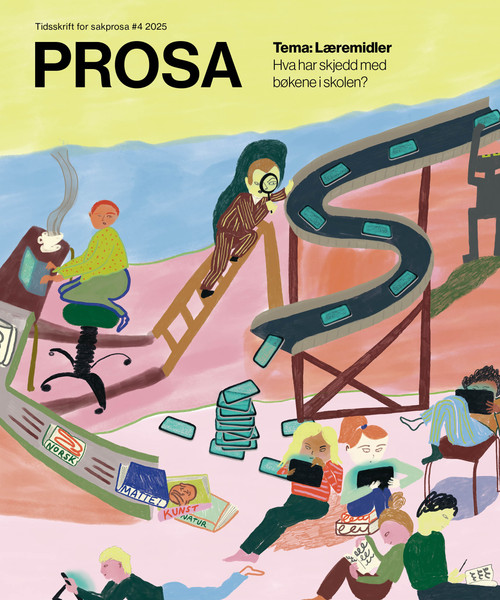

More Popular Science

At the beginning of the 2000s, there was another step-change in Norwegian publishers’ efforts to sell foreign rights. The three largest publishers, Gyldendal, Aschehoug and Cappelen (later Cappelen Damm) established their own agencies and at this point MUNIN was also merged with NORLA. In addition, several independent agencies appeared. In other words more resources became available for foreign sales of Norwegian non-fiction and, in parallel, demand rose at a steady pace.

“Other countries wanted to have Norwegian literature, both fiction and non-fiction,” says Per Øystein Roland, senior adviser at NORLA. “None of our Nordic neighbours can boast of an equivalent increase in demand for non-fiction.”

Even Råkil of Aschehoug-owned Oslo Literary Agency (OLA) confirms that the growth has been significant in recent years. “At the outset popular science books were typically the biggest sellers. Authors like Thomas Hylland Eriksen and Lars Fr. H. Svendsen are good examples: experts who are capable of writing easily accessible books about their field of expertise. Svendsen’s 1999 book Kjedsomhetens historie (The Philosophy of Boredom), for example, has been translated into 25 languages.”

Elisabet W. Middelthon cites Ole Martin Høystad’s book Hjertets kulturhistorie (A Cultural History of the Heart) as another good example of a book about a universal topic, conveyed with a Norwegian approach. The book, from 2003, sold to many countries.

The Norwegian Gaze

Universal topic, Norwegian approach. There seems to be a kind of recipe for success when it comes to Norwegian non-fiction writers who want to head out into the world. Per Øystein Roland points to Morten Strøksnes’s Havboka (Shark Drunk) from 2015, which marks a continuation of this trend.

“In many ways, it’s an extremely local book and yet, at the same time, the topic is undeniably universal. The particular is conveyed in a literary fashion, so it also touches readers who are a very long way away from Lofoten where the action takes place,” says Roland. More precisely, readers in the more than 25 countries the book has now been sold to.

Lars Mytting’s Hel ved (Norwegian Wood), Reidar Müller’s Skogens historie (Howling in the Woods), Torbjørn Eklund’s Stiens historie (History of the Path), Erling Kagge’s Gå (Walking), Are Kalvø’s Hyttebok frå helvete (Hiking to Hell). The list of Norwegian titles with a whiff of resin and bonfires that are sought after abroad could be even longer. Particularly in Germany.

“The Germans love the idea of Norway, and they tend to seek out books that confirm the romantic image they have of Norway as genuine, untouched and authentic,” Roland asserts.

Liberated Women

But nature isn’t the only thing foreign publishers associate with Norway. We also have another literary export that many now envy us: young, female non-fiction authors capable of writing in a natural and knowledgeable way about topics that others might find problematic or shameful. Nina Brochmann and Ellen Stokken Dahl’s Gleden med skjeden (The Wonder down Under) was published in 2017 and has been sold to 35 countries to date. And last year saw publication of Katherina Vestre’s Det første mysteriet (The First Mystery). The book, which quite simply deals with the development of the embryo in the mother’s body from conception to birth, has sold to 21 countries. Even Råkil of OLA represents both titles and has no doubt that the international success of these books is linked to Norway’s image.

“Sexuality, diversity, feminism and anti-authoritarianism. These are important buzzwords for what we can write about in a way that will make an impact out in the world. What’s more these books continue the strong Norwegian tradition of disseminating popular science.”

Per Øystein Roland at NORLA mentions the enormous interest in the TV series Skam (Shame), as an example of something distinctive that other countries associate with Norway. “Young women who are themselves and claim their space. Little doubt that we have potential there,” he says.

Hidden Nipples

But all things in moderation, it turns out. One of the most notable non-fiction success stories from Norway in recent years is Marta Breen and Jenny Jordahl’s Kvinner I kamp (Women in Battle). It’s a graphic book about the history of feminism all over the world, which has sold to almost 30 countries. But in the USA, they were told to please cover up the naked nipples in the Norwegian version, while in Russia the book is sold plastic-wrapped with an 18+ age restriction. Yet Ingvild Haugland and Anette Slettbakk Garpestad of Cappelen Damm agency, who represent the book, defend this kind of censorship. As long as the most important content is not altered, as they put it. Despite a number of challenges when it came to adaptation, Haugland and Garpestad also share the experience that there has been a shift away from nature and towards feminism and other more political topics.

“Books written with a light touch, integrity and preferably in a relaxed and down-to-earth way. At the same time, the topic is still more important than the authorship itself when it comes to the way non-fiction books are assessed for an international market. If the topic doesn’t suit the publishers’ profile, it won’t be bought. No matter how well written it may be. So it’s a matter of finding a topic with broad appeal, but at the same time, the challenge is not to make it entirely impersonal. The interest in feminist literature will probably remain high for a long time to come,” they think.

Flattening-out or Greater Focus?

But is it really possible to plan your way to international success? Even Råkil at OLA doubts it very much. “The books that have become major international successes rarely had an eye to the international market beforehand. They’ve slipped through the window that happens to be open at precisely that moment. Even so, I think we’ll probably get more focused non-fiction titles than before. It’s a matter of the publishing business itself becoming increasingly more international. But in any case, it’s very difficult to write for a market. The market has to find you and your book, not the other way round.”

Per Øystein Roland at NORLA thinks there will be a natural flattening-out in demand for Norwegian non-fiction internationally. “That’s what the experience of other countries that have been guest of honour at Frankfurt shows us. But I think the interest will still remain much higher than it was ten to fifteen years ago. We have a smoothly functioning literary ecosystem in this country and, from that point of view, we have optimum conditions for continued progress. But there are some critical issues. For example, in recent years, NORLA has been able to offer generous translation support to foreign publishers. The onus is on the authorities to ensure that this can also continue beyond 2019.”

Even Råkil is the eternal optimist, describing F 2019 as “a water station with energy drinks.” “We won’t stop here, we’re just rallying our strength for the stages ahead. It’s probably conceivable that the German market will become oversaturated with Norwegian books at some point in the future, but then it’ll be a question of continuing to look for opportunities elsewhere.”

Putting on a Display

So the current framework for international efforts to promote Norwegian non-fiction is entirely different from those fragile beginnings 35 years ago. The market has become much larger and the expectations among authors have also grown. Arne Vestbø, the new secretary general of the NFFO, points out that the diversity and quality of Norwegian non-fiction has grown gradually over many years. “On the international market, the way it works is that if somebody opens the doors, it becomes easier for others to follow. But it’s still the case that plenty of good books don’t break through internationally. It is, first and foremost, the job of NORLA and the literary agents to ensure that pressure is kept up after F 2019,” he says.

He sees the guest of honour project primarily as a celebration of Norwegian literature.

“It’s great to put on a bit of a display. Of course it’s lovely that we’ve achieved this! But Frankfurter Buchmesse is a marketplace first and foremost, and I think it feels pretty remote to the average Norwegian non-fiction author. As a writers’ organisation, our most important tasks are still here at home. Still, it’s nice for us to be able to contribute to the internationalisation of Norwegian non-fiction. We’ve now built up a network of contacts that we must exploit further,” Vestbø says.

His predecessor, Trond Andreassen agrees. “F 2019 is an enormous boost. A new level is being set for everything related to foreign launches. Now it’s just a matter of maintaining that level.”